Editor’s Note: The past year was filled with uncertainty over politics, the economy and the ongoing pandemic. In the face of big changes, people found themselves longing for a different time. CNN’s series “The Past Is Now” examines how nostalgia manifested in our culture in 2022 — for better or for worse.

CNN

—

In 2022, we’re more plugged in than ever.

Cars are fitted with 7-inch infotainment systems, so we can talk, navigate and DJ all at once. Refrigerators have WiFi capability – because why not? Virtual reality is somehow a thing. Even our watches are more than just timekeepers; the latest smartwatches can call 911 if you’re in an accident and track your fertility.

But in the midst of our increasingly digital lives, there’s pushback.

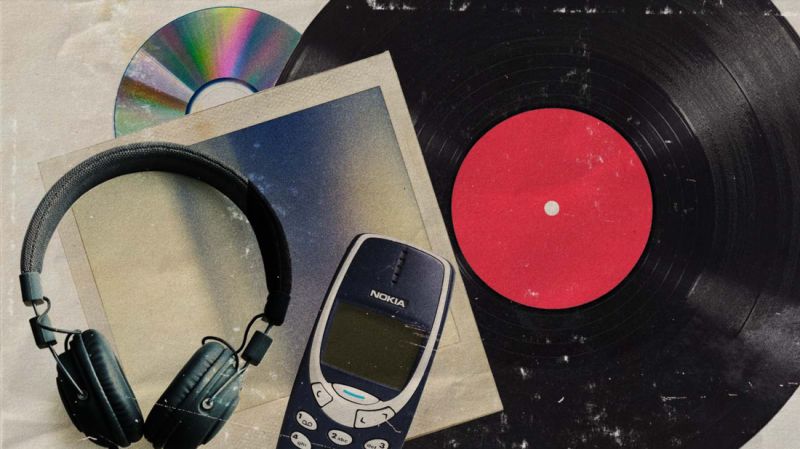

The continued resurgence of physical music is one of the most obvious examples: In 2011, vinyl sales made up just 1.7% of physical sales of music, according to MRC data. By 2021, they made up 50.4%. After years of decline, even CD sales saw a spike in 2021. By mid-2022, revenues from vinyl albums grew 22%, according to the Recording Industry Association of America.

The allure of older formats doesn’t just apply to music. Vintage-seeming headphones are being sold at contemporary fashion stores like Madewell, while Kardashian-approved trendy retro-looking appliances are all over TikTok and Instagram. Polaroid filed for bankruptcy in 2001, but in 2022 it has all but seen a revival – the San Diego Padres even used the instant cameras to chronicle this year’s MLB season.

There’s even talk of a “dumbphone comeback,” as some people ditch their smartphones for models ripped from the early 2000s.

We’re more technologically advanced than ever before. But does our ongoing fascination with the technology of the past indicate we’ve gone too far?

Nostalgia for old technology isn’t a new phenomenon, said Elena Caoduro, a lecturer in film and media at Queen’s University Belfast. But it’s driven, in part, by a longing for an imagined past.

“(We) want to bring back to the present something that existed in the past, or at least imagined they existed in the past,” she said.

She used photo filters on Instagram as an example. Many people use filters, or apps like Huji and VSCO, to make their phone pictures look more like film – smudging the photos, discoloring them or otherwise smearing what was once a perfect image. Even as Instagram filters have fallen out of vogue, celebrities and brands alike have continued to indulge in film aesthetics.

“It is the longing for the physical aspect, the tactile element, of trying to reproduce the signs of a real photograph that people could hold in their hands,” Caoduro said.

But this yearning for the past can idealize it, she said, creating a longing for a time that may not actually have existed. Film photography itself has a history of racial bias, in part due to skin tone standards that were established around White people.

Still, nostalgia sells. Ramon Llamas, a research director at market research firm IDC, recently came across an old-fashioned game console that resembled the Atari 2600, a popular console in the late ’70s and ‘80s. This mockup had the exact same graphics and game play as the original one he’d grown up with, he told CNN.

He loved it, and he wasn’t the only one. Though the console wasn’t outselling the latest Xbox or PlayStation, one store employee mentioned it sold “surprising well,” Llamas recalled.

“Nostalgia is a very, very powerful thing,” he told CNN. “To go back and relive those times and those memories … people are willing to pay money for that.”

Still, there may be other reasons pulling people back into older technology. There are concerns of safety and cybersecurity – Vice President Kamala Harris reportedly forgoes the more popular wireless earbuds for wired ones for those reasons. She’s not alone; a 2022 survey by Deloitte found that more than half of participants are worried about security threats to their smartphones and smart home devices.

There may be physical risks, too. A report by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration found that Teslas, when using driver-assist systems, were involved in 273 crashes over a 9-month period, drawing scrutiny from safety advocates.

But there’s also, among some groups, an increasing desire to disconnect, to unplug. Though smartphones still make up the vast majority of cell phones, some people are choosing to switch to “dumbphones” over concerns of excess screen time. (In 2017, despite the ubiquity of the smartphone, Nokia brought back its popular 2000 model, the Nokia 3310.) Others mourn the days when being reachable 24/7 wasn’t a given, when one could simply disengage.

That feeling may have been exasperated by the Covid-19 pandemic, Caoduro said. For two years, many people spent long stretches of time at home, working remotely and plugged in at all hours. Now, as many emerge, it could lead to a yearning for a seemingly simpler, less connected, way of life.

And yet, not everyone can afford to unplug – or wants to. Demand for older technology may continue to exist, Llamas said, but it doesn’t represent the majority of the market. At the end of the day, he noted, most people want the convenient perks of technology. They’re annoyed by the tangled earbud wires, the clunky cell phone, the pixelated graphics.

Tech like vinyl and CDs may have their nostalgic, tangible perks. But if you just want to listen to music, it’s so much easier to stream.